Growing up as a young lad in a rural Kenyan village some decades ago, was full of fun. It was a life rich in local health traditions that each child was expected to master and apply. However, as the rest of the world opened up to me during the period I was away in high school, Kenyan and Foreign Universities, I was faced with new health issues and approaches that were more intriguing and quite different from what I had got used to. Today, I look back with nostalgia on some of the simple health tools and health education that were passed down to me by my grandparents, and which are now relevant, particularly during this Covid-19 pandemic. In those days, greater emphasis was placed on washing of hands, cleanliness of your clay- or wooden-based utensils, clean cooking and eating area. You were also encouraged to clean your hands after any handshake so that you avoid contaminating yourself and the environment where you are. These were simple instructions then, but with the current Covid-19 infection, I find myself being reminded by the health authorities to apply almost similar regimes in controlling the spread of covid-19 infection, a regime my grandparents had long mastered in their yonder years.

Nonetheless, my work as lecturer and researcher in dentistry at the University of Nairobi and my association with DeRouen Center for Global Oral Health, has given me yet another opportunity to understand better the importance of global oral health and especially as it relates to the oral health of the child. The research collaboration I have enjoyed with Dr. Ana Lucia Seminario, the Director of DeRouen Center for Global Oral Health, together with other colleagues affiliated with this Center, has further availed to me additional opportunities to this end, and even my current activities in relationship to the oral health of the vulnerable children from communities living in my own country, Kenya. I now understand their greatest oral health needs and priorities, given that many of these children come from communities that have their own peculiar challenges and health traditions.

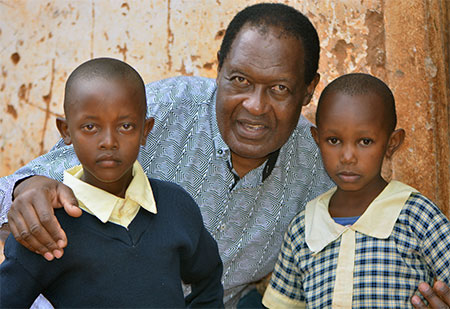

A couple of years ago, I was shocked to learn of an existing traditional health practice in some communities in Kenya, and in other East and Central Africa nations. This practice, I learnt, goes way back to the early 20th century when some tribes began applying it to their children as a cure for childhood diseases like fever, vomiting and diarrhea. This practice, otherwise called Infant Oral Mutilation or IOM, affects millions of children from this region. It involves the gouging of developing primary canines of a child younger than 24 months. The developing primary Canine tooth germs are considered to be ‘WORMS’ that cause childhood illnesses. The scary part of the practice is that the operators, who are usually traditional healers/herbalists, religious leaders, traditional birth attendants and even family members, use unsterile crude instruments (sharpened, stones, bicycle/umbrella spokes, nails, razor blades, wires, etc.) to gouge out these canine tooth germs. No painkillers, sedatives or anesthetics are used during the operation, thus predisposing this child to excruciating pain, besides hemorrhage, shock, septicemia, tetanus, anemia, osteomyelitis, meningitis, hepatitis B and HIV/Aids. As a result, some children have died from IOM practice, and those who have survived have ended up with unnecessary dental spaces within their jaws (see Figure 1), displaced permanent successor teeth, developmental defects of permanent and primary teeth and psychological trauma. Furthermore, with the advent of Covid-19 pandemic, the close contact made amongst those involved during the operation predisposes them to this infection, since the use of personal protective equipment does not form part of the armamentarium. The suffering these innocent children have to go through has made me to be an advocate for its eradication, making me travel to various Kenyan rural areas in an effort to help the communities understand about the dangers associated with this archaic practice to the growing child.

Unfortunately, this primitive, painful, barbaric and harmful practice called IOM has evolved into a global health concern, due to migration/translocation of some of the members from these communities to other countries where IOM does not exist. These migrants have continued to subject their new-born children to IOM in their adopted countries or trek back to their communities in Africa to have the child go through the practice before returning back. Consequently, IOM can now be found in these African migrants living in the USA, Canada, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, UK, Israel, Australia, New Zealand, etc, making IOM “a global public health and child abuse” issue and further a violation of the UN Convention on the rights of the child, that needs to be condemned by all who care and defend and protect the quality of health of the child. You could be the next advocate for its eradication, but the fact is that these helpless children require this protection now, more than ever.