Refugees often experienced trauma in their home country, and during the migratory process to neighboring countries and refugee camps. Studies have shown that refugees have worse oral health than the vulnerable and underserved populations of their host countries. Furthermore, oral care might consist of just emergent removal of teeth and or abscess treatment with antibiotics. Additionally, many host countries have no pediatric oral care or enough fluoride in water to prevent tooth decay. By the time their migratory process ends in the western world, many face new problems, including learning a new language, finding a job, educating themselves and their children, and generally adapting and acclimating to their new environment. By the time refugee families are in the United States, oral health can seem unimportant compared to the accumulated trauma before their final resettlement.

Refugees often experienced trauma in their home country, and during the migratory process to neighboring countries and refugee camps. Studies have shown that refugees have worse oral health than the vulnerable and underserved populations of their host countries. Furthermore, oral care might consist of just emergent removal of teeth and or abscess treatment with antibiotics. Additionally, many host countries have no pediatric oral care or enough fluoride in water to prevent tooth decay. By the time their migratory process ends in the western world, many face new problems, including learning a new language, finding a job, educating themselves and their children, and generally adapting and acclimating to their new environment. By the time refugee families are in the United States, oral health can seem unimportant compared to the accumulated trauma before their final resettlement.

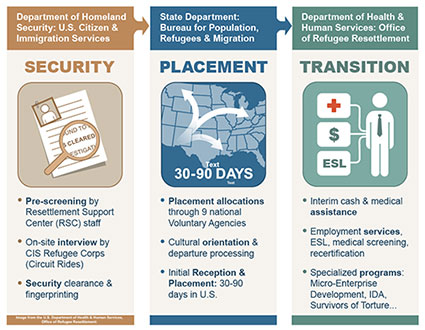

Washington state ranks third in the United States in the number of refugees it accepts. As a leader in the resettlement of refugees, identifying and addressing severe oral health disease is vital to early treatment and preventing further deterioration. With the generous support of Arcora Foundation, the refugee oral health project seeks to understand the processes of the initial refugee medical healthcare screening. Currently, the dental screening part of this process is just one question with a yes/no answer, asking if they have any dental problems. Given the cultural and linguistic differences and the fact that some refugees have never seen a dentist, it is essential to develop an evidence-based questionnaire to help identify severe oral health disease.

There are seven clinics that are responsible for the initial medical screening of the new refugees that arrive in Washington state. Five of these seven clinics have the capability to be refugees’ primary medical health care home. The potential for establishing oral health care referral, good oral hygiene practices through education, and follow-up referral is an opportunity that cannot be missed. However, establishing a good oral health screening process embedded within a refugee’s first contact with the healthcare system during the initial medical screening can identify problems and direct them towards oral health care immediately. We hope the refugee oral health project that UW’s Timothy A. DeRouen Center for Global Oral Health is conducting with funding from Arcora Foundation is the first step in strengthening the health status of arriving refugees in Washington.